Possibility Thinking for Social Change

Picture

These bricks relate back to the Building Site photo in Topic 1. They are the unformed, the un-made. To me, they symbolise the possibilities open to us. Yes they are bricks. but what might they be? A house, a wall, a tower, an archway or something that doesn’t have a name yet?

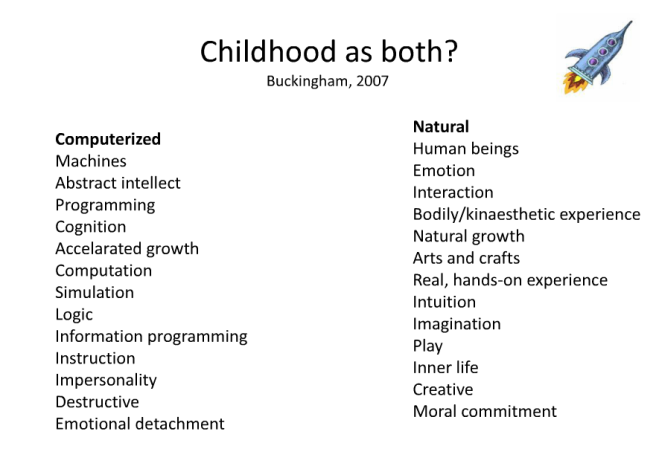

Possibility Thinking is a wonderfully simple concept; “A democratic notion of creativity in an everyday context” (Craft and Chappell, 2014). Valuing question-asking, improvisation, risk-taking, playfulness and imagination; what educational institution wouldn’t want to include these in their day to day existence?

Possibility Thinking in a School Context

Craft and Chappell (2014) look at two institutions in Exeter that implement Possibility Thinking in the running of the school. This made me reflect upon the overarching aspect of this style of thinking. PT can be applied in a single classroom activity, or in the class charter, departmentally, as a whole school policy, as a policy between affiliated schools, as a national policy or a global policy! There are no limits; the simplicity of the notion makes it so easy to apply in a variety of contexts.

In both cases, schools bucked the trend of increasing drive towards performativity and instead embraces a playful, creative curriculum that inspired passionate learners. When questioned about their results the headteacher of St Leonard’s was proud to tell us that many of her children excelled at not only the SATs but also the 11+ to gain entry to the local grammar school.

In both schools PT was modelled by the Head Teachers, providing the space and time for staff to experiment and think creatively too. This permeated the classroom context.

Both schools supported creative questioning and were action focused, encouraging staff to run personal Inquiry projects and to focus primarily on teaching and secondary on paperwork.

The schools felt a strong sense of pride in their ‘difference’ , their individual identity and a tangible positivity that what they were doing was right.

Nonetheless, the report (which was primarily based around interviews) noted that neither school took particularly huge risks, so risk taking was not a factor of PT that permeated the school. I don’t particularly agree with this; in simply breaking away from the norm these schools are taking risks. In giving teachers the freedom to explore, they are taking risks. Even the play equipment which would have been deemed to risky for Health and Safety (the trikes and bikes) at St. Leanords could be deemed as risk taking! I think that in terms of this study it’s a little unjust to say these schools weren’t risk taking on the basis of interviews.

What is creative change?

There were many ways in which the schools bought about creative change:

- Strong ethos/values/principles

- Challenging/complex/controversial drive for change – a support system, a gradual move in the right direction

- Driven by children and school community – including parents and students in decision making

- Staff ethos – a stable staff body, all driving for change , play to their strengths

- Digital media – being at the forefront of technology – using google cloud etc blogging – ‘mindful that it doesn’t take over’ though.

How were they going about it?

- Operating ‘In a bubble’ – protecting your school, steering towards a vision, preventing government strategies from intervening too heavily.

- Navigating performativity – research based principle gives confidence – don’t let the drive for performance undermine the vision of the school. NC only 20% of what they do.

- Focus on children’s well being; their interests, wants and needs. Adapting their route based on this – responsive

- Relating to other schools around them; creating a learning community – schools maintain their own pathways but offer support.

Reflections

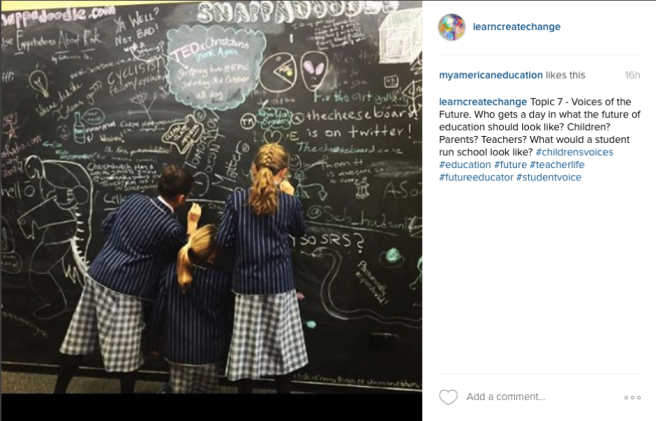

I’m really heartened to see this drive for creative change in British schools. It echoes what I’ve seen in New Zealand. The school’s maintained a strong sense of self whilst also relating to others around them through the sharing of facilities and best practice amongst teachers.

I believe firmly that the less importance places on tests, the better. Yes data is needed to see how children are progressing, but this is not the only growth measurement. Testing should be subtle and shouldn’t be a cause of stress for teachers or students. Instead, both parties should feel happy and confident in the content covered and progress made by students.

Things I noted:

- Wonder room – a maker space type zone? (how much was this used, looked a little TOO pristene!) wonderful to dedicate a space to exploration though

- Lots of male teachers – perhaps this open, less judgemental environment suits them? Perhaps it’s Jo’s drive to deliver a versitile and diverse learning experience.

- A sense of collaboration between teachers, TAs and the management teams – I liked the observation schedule, I think that this would keep you on your toes, allow flowing dialogue about your lessons and allow you to appreciate your colleagues and their expertise. So often observation is seen as negative!

- Checking of standards, peer checks as well as head of year. Subject leaders as responsible too – is this responsibility borne equally (ish)? It seems as though everyone was responsible for one area and they enabled others to work well.

- Head bore ultimate responsibility for her staff “If it doesn’t work, I am accountable, I take responsibility. If it does work, they are responsible, they claim it!” – I’ve experienced 2 types of head; one who put staff first and one who put parents first. The staff need to feel comfortable and supported, the parents will be happy with the by-product of happy staff which is happy children.

- The school displays were really engaging – as a parent, I’d know exactly what my child was focusing on and would hopefully be able to help.

- Use of experts – again, really similar to Lane Clarke’s Inquiry – using experts in the field to inspire. Combining your expertise.

- Honesty around who you are as a learner – reflecting on your learning style.

- Engagement centred around finding out what interested teachers and students. Asking, What do you want to learn? Instigating wonder – you don’t always need an objective – give them the opportunity to find out.

- Teaching partnerships based on complimentary strengths

Questions arising?

Conflict and confrontations – between staff/visions/parents – how are these handled?

The role of technology in change – is everyone equally optimistic or are there sceptics to balance out arguments?

How do changes take place? Organically? How easy for staff to lead a change?

Examples of individual research projects at the school – staff Inquiries?

Why don’t other schools do this? Is it a fault in leadership? A lack of support?

Picture

Picture